Tiny Tech: Innovations Reshaping Neonatal Care

By Juliane Crafton, MSN RNC-NIC

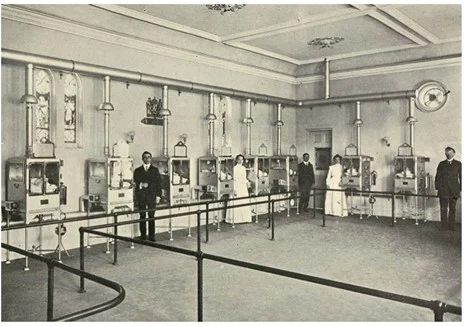

Imagine—on a bright summer day in 1901, you walk into the Pan-American Exposition, a world’s fair in Buffalo, New York. Struck by the foreign architecture and bold colors, you explore. From fine art to horticulture to a Native American village, all the western hemisphere’s best advancements are on display. Soon, you find yourself in a room lined with unfamiliar machines and nurses, showcasing the tiniest babies you have ever seen (Figure 1). A nurse places an oversized diamond ring around an infant’s wrist to show how small they are (Silverman, 1979).

Figure 1

Babies in Incubators at the Pan-American Exhibition in 1901 in Buffalo, NY

The incubator was a landmark innovation, marking the beginning of a technological revolution in neonatal care (“Baby incubators at the Pan-American Exhibition,” 1901; Reedy, 2003). Over the 20th century, the incubator was joined by a wave of other life-saving technologies, such as pulse oximetry, phototherapy, and transcutaneous carbon dioxide monitors (Brennan et al., 2019; Hay, 2005; Parga & Garg, 2017).

Today, the pace of innovation is accelerating, demanding that neonatal nurses continuously adapt to improve safety and efficiency in caring for these tiny patients. This rapid evolution not only introduces new tools for care but also fundamentally reshapes the neonatal nurse’s role, demanding new skills in data interpretation and raising complex ethical considerations.

What’s New and What’s Coming

The technological boom of the late 20th century ushered in a new era for neonatal care. While innovations like transcutaneous carbon dioxide monitors and ECMO are now widely used, their adoption is relatively recent, becoming standard only in the past few decades. Now, even more sophisticated technologies are emerging.

Krbec et al. (2024) describe emerging innovations, including remote sensing technologies that could rid the NICU of wired monitoring of vital signs. Developments in camera technology and improved affordability have led to an increase in the study of their use in health care. The focus has been on adult applications with pilot studies exploring the use of visible light, infrared light, and radar-based technologies to monitor vital signs (Chung et al., 2020; Krbec et al., 2024). Chung et al. (2019) describes a wireless epidermal system with in-sensor analytics studied for neonatal use. Go to https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aau0780 to see images of the system on a neonate. Preliminary study has shown advanced capabilities in monitoring, along with a skinlike profile that reduces skin breakdown and reduces barriers for skin-to-skin contact.

Beyond passively monitoring vital signs, the next frontier involves artificial intelligence (AI) actively interpreting this data. Though there are many challenges and limitations, AI deep learning models have shown promising capability to detect features like subtle changes in movements or skin color and correlate them with vital sign changes and various pathologies (Krbec et al., 2024). Kwok et al. (2022) describes the use of deep learning models for prediction of neonatal mortality and morbidity, identifying patterns within data, interpreting data in relation to neuroimaging, performing image recognition, and predicting responses to neonatal treatment. Many NICUs already use some combination of early warning systems and scoring models to determine risk and predict adverse outcomes. Adding the additional layer of AI to deepen the ability to predict has great implications for providers and caretakers of this patient population.

Telehealth is emerging as a powerful tool to democratize neonatal expertise, bridging the critical gaps of distance and resources that can impact care. Through applications like remote specialist consultations and virtual grand rounds, these systems connect providers across different levels of NICUs, fostering collaboration that leads to improved outcomes. For instance, a tele-NICU program in Arkansas gives patients in rural hospitals unprecedented access to leading specialists through bidirectional information sharing (Arkansas Children’s, 2025). This model is not unique; similar pilot programs are being implemented in NICUs worldwide, demonstrating a global shift toward leveraging technology to overcome geographical barriers to care (Arkansas Children’s, 2025; Wagenaar, 2025).

On the cutting edge of regenerative medicine, three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting holds profound potential for neonatal care. Tottoli et al. (2020) describe a technique to create custom hydrogel scaffolds by “printing” a combination of biomaterials and a patient’s own cell cultures directly onto a wound. See Figure 5 in Tottoli et al.’s 2020 article. The resulting structure acts as a bioactive dressing—a living bandage that actively supports and accelerates skin regeneration, integrating concepts from cell therapy and tissue engineering. Although clinical applications for infants have not been thoroughly explored, the implications are significant (Tottoli et al., 2020). For premature infants with extremely fragile skin prone to injury, 3D bioprinting could one day offer a revolutionary approach to healing, minimizing scarring and the risk of infection. For premature infants with extremely fragile skin prone to injury, 3D bioprinting could one day offer a revolutionary approach to healing, minimizing scarring and the risk of infection.

Evolving Tools, Evolving Roles

The integration of these emerging tools does more than change workflows: it fundamentally redefines the identity and responsibilities of the neonatal professional. Already hands-on caretakers, nurses are evolving to add new responsibilities as critical data interpreters and technology managers who must validate predictions and facilitate care alongside sometimes-remote specialists. This evolution brings many important ethical considerations. The use of AI shows promise for predicting adverse outcomes but raises questions about algorithmic bias, data privacy, and accountability when a predictive model is wrong. Similarly, while telehealth can give low-access regions access to specialists, it introduces challenges in maintaining the human connection essential to care and ensuring equitable access for families with technological or resource barriers.

The emerging role of the neonatal caregiver is not just to be technologically proficient but to be a vigilant, ethical advocate, ensuring that these new, powerful tools are applied in a way that is safe and equitable and enhances compassionate, patient- and family-centered care.

Conclusion

From the simple, life-sustaining warmth of the first incubators to the complex predictive power of AI learning models, the evolution of neonatal care is a story of technological advancement. Innovations like remote sensing, telehealth, and 3D bioprinting are the tangible future, promising to further improve survival and long-term outcomes for the most fragile infants.

As these tools are integrated into practice, they demand an evolution in the role of the neonatal nurse: from a hands-on caregiver to a sophisticated clinical data analyst, technology facilitator, and ethical guardian. The ultimate challenge and opportunity lie not just in adopting the new technology but also in thoughtfully combining it with compassionate, human-centered care to ensure that every innovation serves the ultimate goal: helping the tiniest humans thrive.

References

Arkansas Children’s. (2025, June 4). TeleNICU program brings Arkansas Children’s NICU care across the state. Arkansas Children’s Blog. https://www.archildrens.org/blog/telenicu-program-at-ac

Baby incubators at the Pan-American Exposition. (1901, August 3). Scientific American, 85(5), 68–68.

Brennan, G., Colontuono, J., & Carlos, C. (2019). Neonatal respiratory support on transport. NeoReviews, 20(4), e202–e212. https://doi.org/10.1542/neo.20-4-e202

Chung, H. U., Kim, B. H., Lee, J. Y., Lee, J., Xie, Z., Ibler, E. M., Lee, K., Banks, A., Jeong, J. Y., Kim, J., Ogle, C., Grande, D., Yu, Y., Jang, H., Assem, P., Ryu, D., Kwak, J. W., Namkoong, M., Park, J. B., … Rogers, J. A. (2019). Binodal, wireless epidermal electronic systems with in-sensor analytics for neonatal intensive care. Science, 363(6430). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau0780

Chung, H. U., Rwei, A. Y., Hourlier-Fargette, A., Xu, S., Lee, K., Dunne, E. C., Xie, Z., Liu, C., Carlini, A., Kim, D. H., Ryu, D., Kulikova, E., Cao, J., Odland, I. C., Fields, K. B., Hopkins, B., Banks, A., Ogle, C., Grande, D., … Rogers, J. A. (2020). Skin-interfaced biosensors for advanced wireless physiological monitoring in neonatal and pediatric intensive-care units. Nature Medicine, 26(3), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0792-9

Hay, W. W. (2005). History of pulse oximetry in neonatal medicine. NeoReviews, 6(12): e533–e538. https://doi.org/10.1542/neo.6-12-e533

Krbec, B. A., Zhang, X., Chityat, I., Brady-Mine, A., Linton, E., Copeland, D., Anthony, B. W., Edelman, E. R., & Davis, J. M. (2024). Emerging innovations in neonatal monitoring: a comprehensive review of progress and potential for non-contact technologies. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 12, 1442753. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2024.1442753

Kwok, T. C., Henry, C., Saffaran, S., Meeus, M., Bates, D., Van Laere, D., Boylan, G., Boardman, J. P., & Sharkey, D. (2022). Application and potential of artificial intelligence in neonatal medicine. Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 27(5), 101346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2022.101346

Parga, J. J., & Garg, M. (2017). Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in neonates: History and future directions. NeoReviews, 18(3), e166–e172. https://doi.org/10.1542/neo.18-3-e166

Reedy, E. A. (2003). Historical Perspectives: Infant Incubators Turned “Weaklings” into “Fighters.” The American Journal of Nursing, 103(9), 64AA-64AA. https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/citation/2003/09000/infant_incubators_turned__weaklings__into.34.aspx

Silverman W. A. (1979). Incubator-baby side shows (Dr. Martin A. Couney). Pediatrics, 64(2), 127–141.

Tottoli, E. M., Dorati, R., Genta, I., Chiesa, E., Pisani, S., & Conti, B. (2020). Skin Wound Healing Process and New Emerging Technologies for Skin Wound Care and Regeneration. Pharmaceutics, 12(8), 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12080735

Wagenaar, J., Van Beek, R., Pas, H., Suurveld, M., Van Der Linden, N., Broos, J., Kleinsmann, M., Hinrichs, S., & Taal, H. R. (2025). Implementation and effectiveness of teleneonatology for neonatal intensive care units: A protocol for a hybrid type III implementation pilot. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 9(1), Article e002711. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2024-002711